By Sabrina Fay

The ocean, when it is near, is always a society's biggest asset. From the ocean, the navy strikes at your enemies with vicious precision and power. From the ocean, your pioneers sail away to conquer other lands and reap their spoils. From the ocean, your people gain their lifeblood in the fish that swim to and fro. From the ocean, you get a sense of tranquility that comes only with the taste of salt on a sea breeze. One of our most studied and continually emulated societies, Ancient Greece, grew to such great power and prestige thanks to its strong connections with the ocean.

Art

Much of Greece's art was inspired by its people's affinity for the sea. Upon pots and clay, and in mosaics like the one displayed, they transcribed images of ships, fish, and Poseidon (Greek god of the sea). A great deal of Ancient Greece's mythology, from which its temples and artworks were based, centers around the sea. Just one of these myths states that from the ocean waves Poseidon created the horse, while another relates that Greek goddess of love and beauty, Aphrodite, was born from sea foam when the genitals of Ouranos fell to earth. Slightly gross details aside, be they directly related to the sea, like Poseidon, or only created from it like Aphrodite and the horse, many of Ancient Greece's objects of greatest reverence and inspiration lead back to the surf. Much of this art was brought to other lands packed amongst Grecian staples like olives and wine. Speaking of which, the export of those staples and import of others was made possible for the Greeks because of their access to the sea.

Currency and Laws

Sea trade greatly facilitated currency development in Ancient Greek city states. Special currency was even created for certain products, namely grain. So important was grain to feeding the Athenian people, and so unavailable was it in the Greek mainland (due to the untenability of the terrain, gone into more detail in the next section), that special officials were designated to assure shipments' prices and quantities, and special grain buyers called "sitones" were established. Preventing the import of grain, or the re-exportation of it, was strictly forbidden and punishable by death.

Agriculture

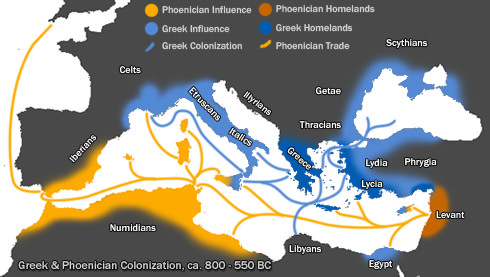

The Ancient Grecian mainland lay upon the Mediterranean sea, uniting civilizations like Athens, Rome, and islands like Crete through the open water between them. Though the Greeks could easily grow grapes (and by extension, wine) and olives, and had great luck with sheep (one of the most powerful objects in their mythos was a golden fleece after all), their rocky terrain made other crops very difficult to farm. Cattle and oxen, needing wide and grassy spaces to roam, were not available in large enough supply to sustain the civilization. And so, like any advanced society, they turned their attention outward for those coveted resources. Wine, olives, honey, pottery, and figs went outward, while grains, pork, wood, and papyrus came in. Wood was especially useful in shipbuilding, coming in from Macedonia and Thrace and stimulating the cycle of Greece's sea-based economy even further with more ships and the jobs created by a ship-making industry. The map below illustrates some of Ancient Greece's trading partners and practices:

From the art upon their pottery to the alphabet they developed with influence from encounters with Phoenician sea traders, a great deal of the Ancient Greeks' success was due to and supported by the sea. All of it of course goes to show the importance of bodies of water to a civilization's growth, relevant not only in the study of the past but in the practices and plans of the present and future.